How to Web Scrape for Journalists — Beginners Guide Final Part

Part 3 in a series by Ashlyn Poole

Hi all, and welcome to the third and final part of my beginner's series on web scraping for journalists! I’m glad you’re back, which must mean you’re just as eager to see this code up and running!

A quick piece of advice: Hold onto that feeling you’re about to get at the end of this article. It’s an emotion that only comes at the tail-end of a meticulous code, when your program’s functionality finally aligns with the vision you had for it. You saw it in your mind before your fingers ever pressed down on the keyboard to type that first line of script —- and it won’t be long until you see it executed right in front of your eyes.

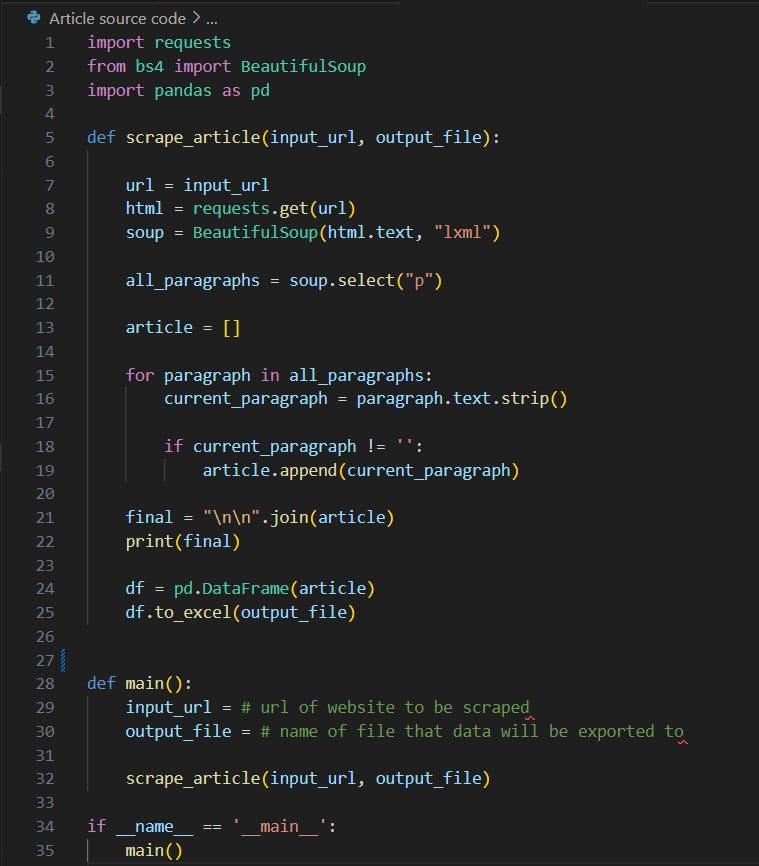

Before we pick up where we left off, I recommend you take a moment to check out what your output looks like at this point in the code. To do this, write out a print statement and run the code, like this:

print(article)

You should see a list of all the paragraphs that are in the article. A list is a data structure in which the elements are comma-separated. There are a bunch of different methods we can use to manipulate lists. Right now, we are going to focus on the .join() method.

We are going to put all of our paragraphs together into a new variable called final. This variable represents the string that makes up the full article. We do this using the .join() method, which combines all the elements in an iterable data structure, a list in this case, with a separator, a string that you must specify before the .join(). The iterable data structure goes inside the parentheses. Here’s how it would look in this code:

final = ‘\n\n’.join(article)

The ‘\n\n’ acts as our separator. For those who are unfamiliar with \n, it is a newline command that tells the computer to move to a new line. The reason why I put two is so there is an empty line in between each paragraph for formatting purposes. If you do just one \n, there is no line in between each paragraph, which might make it difficult to identify the beginning of a new paragraph.

Now, there’s just one step left before we export our data. It’s a simple one:

print(final)

Use this command to check and make sure that your output looks right. If something is off or you’re getting an error, go back through the steps and make sure you followed them all correctly. If you still have issues, copy and paste your code into ChatGPT and see if it can locate the error.

Once the article looks how you want it to look, we’re going to export it into an Excel file. The thing about exporting into Excel using the DataFrame method is that you have to export some sort of data structure, meaning it won’t work with just a string. Since final is a string, we are going to export our article list. The output will thus be an Excel file where each row is one paragraph of the article. Here’s how to do it:

df = pd.DataFrame(article)

df.to_excel(‘first-scrape.xlsx’)

We just created a new variable called df (for DataFrame) that is a pd DataFrame object. To note, pd is just an alias for the pandas library. The function of this first line of code is to convert our article list into a DataFrame.

Once we have our variable set up, we can call the .to_excel() method, which takes in the filename as an argument. This can be anything as long as it ends with ‘.xlsx,’ which is the standard Excel format. I named it ‘first-scrape.xlsx’ for you, but you can change it if you like. In essence, the second line of code exports the DataFrame into an Excel file, which will be titled whatever name is found within the parentheses. Note that the filename must be in quotations.

If a file with this name already exists on your computer, the file will be overwritten with the new data. If it doesn’t exist, a file with this filename will be created. To locate this file on your computer, find the filename in the left-hand Explorer panel on VS Code, right-click on it, and press ‘Reveal in File Explorer.’ If you aren’t using VS Code, look up the steps for your specific IDE.

While exporting into Excel isn’t particularly ideal when working with just one article, being familiar with this process will be useful to you when working on more complex projects. As a very base-level example, if you are scraping an article for the name of the reporter, the published date, and a link to the article, you will need three Excel columns rather than one. In this case, an Excel sheet would be way more useful for organization than in our example.

And that’s a wrap on our code!

I’m not going to get into automation on this issue, as that incorporates RSS feeds and task scheduling on your computer. However, once you learn how to scrape a page, you do realize that skill by itself isn’t very useful for most projects. You are going to need to find a way to scrape large amounts of data periodically, without having to manually run the code.

With that being said, you won’t be able to understand RSS feeds and automation without first understanding the pattern behind a webpage’s code. Hence why I wrote this article. And once you truly do understand the pattern, every webpage becomes its own “puzzle,” as Newsroom AI Automation Engineer at Hearst Newspaper Ryan Serpico puts it. The AI Team is privileged to collaborate with Ryan on our Source Directory bot, and his insights have been invaluable to us.

I hope you feel incredibly accomplished after scraping your first webpage! I’d encourage you to keep practicing your coding skills and keep on the lookout for any advanced web scraping articles I might publish. In the meantime, there are plentiful resources all over the wide web that’ll help take your code to the next level. If you’re interested, a fun next step could be to write a code that scrapes the Daily Texan’s main page, rather than just a single article from their site. And if you ever get stuck, you can always just ask ChatGPT to identify your error or explain the steps in a way that makes sense.

If you’re anything like me, this process made you super excited about just how many opportunities a simple code can open up for you. That just makes you want to dive in even deeper, so you can create something even more innovative and dynamic. Stay curious, and remember that this is a process of trial and error. You’ll only ever come out the other side with something new, something that you didn’t have before. So what’s there to lose?

Thanks to all who read until the end of this series, or interacted with any part at all. I know you can create anything that you think up in that marvelous mind of yours —- just put in the work and watch it come to fruition. Happy coding!